I'd planned to show you what I did with that lovely blue ink I mixed a few weeks ago but I've gotten side-tracked with giving eco-dyeing a try. Eco-dyeing is using the natural pigments in plant material -- leaves, roots, bark, etc. -- to dye either fabric or paper. In it's simplest form it's nothing more than simmering the plant material in water to create a dye bath.

Since not all plant matter is safe to eat and some of it is downright toxic, it's best to have dedicated pots and utensils that you use only for dyeing. Eager to get started, I used our regular cooking pots and was careful to only experiment with edible produce like kale and orange rinds. Here fabric is simmering in an avocado pit and skin dye bath:

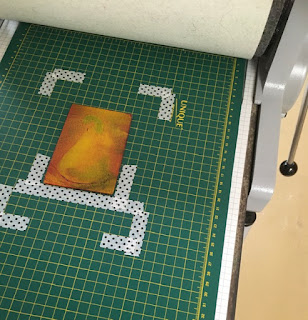

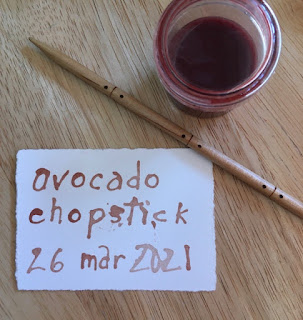

Initially, my aim was to produce ink rather than dye. Following instruction from Make Ink: A Forager's Guide to Natural Inkmaking by Jason Logan, artist and owner of The Toronto Ink Company, I tried a small batch of avocado pits and skins and got this:

Two tiny pots of ink. Not green or brown as expected -- but a rusty-peach! I added gum arabic as per the book's advice (I assume to give the liquid a bit of body) and tried it with a dip pen. With not much luck. The ink seemed too thin to cling to the nib and I got only faint scratchy lines. I had better luck with something stouter like a chopstick, below, or the trusty eye dropper, as in the quick tulip sketch.

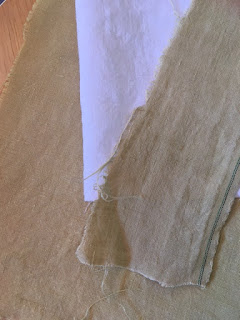

Then I tried dyeing fabric, with remnants of white linen and cotton I had on hand, and got this:

Unfortunately, photographing the subtle colour of the plant dyes is proving difficult. You'll have to take my word I got a lovely range of soft peachy pinks.

By now I had a library book by British expert Babs Behan, Botanical Inks: Plant-To-Print Dyes, Techniques and Projects (which, despite the title, is more about dyeing fabric) and thrift store pots and utensils so I felt comfortable adding modifiers to the dye bath like vinegar, baking soda or iron water (a brackish solution obtained by soaking rusty metal in vinegar). My first try was with a fifty-nine cent carton of marked-down baby kale. The samples likely appear beige but the true colours are more towards a beige-green.

Be forewarned! This eco-dyeing is so accessible -- foodstuffs from the kitchen, plants from your own yard -- it's utterly addictive. I tried the broth leftover from cooking black beans from scratch, a big handful of the papery skins from our garlic crop, and the prunings from a Japanese barberry bush and a lilac -- with encouraging degrees of success. Here are linen samples with the black bean and the garlic.

Below, are Japanese barberry (which produced several interesting yellows -- unfortunately everything looks beige in the photos), followed by a second batch of avocado dye. This time I paid attention to the directions (like soaking the fabric in water for 24 hours before dyeing and then leaving in the dye pot a further 12 hours -- requires patience!) and got even deeper saturation.

The range of pinks and purples came from using modifiers. Vinegar pulled the pink towards orange. The iron gave those rich purples. Alkaline baking soda upped the rosy colour. So many colours from one dye source!

I'm enamored with the holistic, thrifty nature of eco-dyeing. It's low-tech and inexpensive, can be done with a cold water extraction (as opposed to using heat from a stove to speed up the process), and any water used can be returned to the garden. It gives a second life to pits and parings destined for the compost and is a rewarding connection with the outdoors. I find myself appreciative of trees and weeds and even kitchen waste! As I write, cherry bark (from a dead tree cut down for firewood), wild maple twigs, Douglas Fir cones and used coffee grounds are soaking in the greenhouse. The very definition of "slow dyeing". On sunny days it gets up to 30 degrees Celsius in there and, if I'm patient enough, that daily warmth and time will release the pigments.

Here's the stack of samples I've accumulated so far. The colours are subtle and varied, yet harmonious.

This might turn out to be a short-lived infatuation but I keep stumbling across yet another eco-dyeing source. I've just learned lichens produce the most exciting purples! And that you can dye with mud and even cow patties! Let's hope I don't go that far...